What on earth are the pseudovectors?

1 Introduction

In physics textbooks, we often come across the terms “pseudo-vector” and “pseudo-scalar.”

In fact, on a 3-dimensional manifold, a “pseudo-vector” is the exterior product of two tangent vectors, denoted as $v\in T_pM\wedge T_pM=\bigwedge^2(T_pM)$, while a “pseudo-scalar” is the exterior product of three tangent vectors, denoted as $s\in T_pM\wedge T_pM\wedge T_pM=\bigwedge^3(T_pM)$.

When equipped with an inner product (or non-degenerate bilinear form), there exists a Hodge duality between $\bigwedge^2(T_pM)$ and $\bigwedge^1(T_pM)$, which leads us to mistakenly consider the pseudo-vector as a vector. Similarly, due to the Hodge duality between $\bigwedge^3(T_pM)$ and $\bigwedge^0(T_pM)$ (scalar fields), we mistakenly treat the pseudo-scalar as a scalar.

In fact, a pseudo-vector on a 3-dimensional manifold is mathematically equivalent to a 2-vector (bivector). It is similar in definition to a 2-form, with the distinction that a 2-vector belongs to the exterior product of the tangent space, $v\in\bigwedge^2(T_pM)$, while a 2-form belongs to the exterior product of the cotangent space, $\omega\in\bigwedge^2(T_p^*M)$.

2 Space Inversion

Recalling why we call “pseudo-vectors” pseudo-vectors in the first place. It is because they exhibit exotic behaviors under space inversion transformations. However, if we consider them as the exterior product of two vectors, all the peculiar behaviors can be explained.

Specifically, as shown in the figure below, under a space inversion transformation, the magnetic field reverses its direction. It’s similar to you moving in one direction, but the reflection of you in the mirror moves in the opposite direction, which is a spooky and paranormal event.

The magnetic field is a bivector. If you consider it as a vector, you will encounter this spooky phenomenon in the picture: the magnetic field takes a look in the mirror and finds its head turned into feet.

In fact, the magnetic field at point $p$ is not a vector but a bivector, denoted as $B|_p\in (T_pM)\wedge (T_pM)$. Its basis consists of $\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\wedge \frac{\partial}{\partial y},\,\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\wedge \frac{\partial}{\partial z},\,\frac{\partial}{\partial z}\wedge \frac{\partial}{\partial x}$.

So, there is no paranormal event happening. Under a space inversion transformation, both vectors corresponding to the magnetic field actually point in the correct directions. It’s just that humans insist on using the right-hand rule and treat a bivector as a vector, which leads to the appearance of this strange phenomenon.

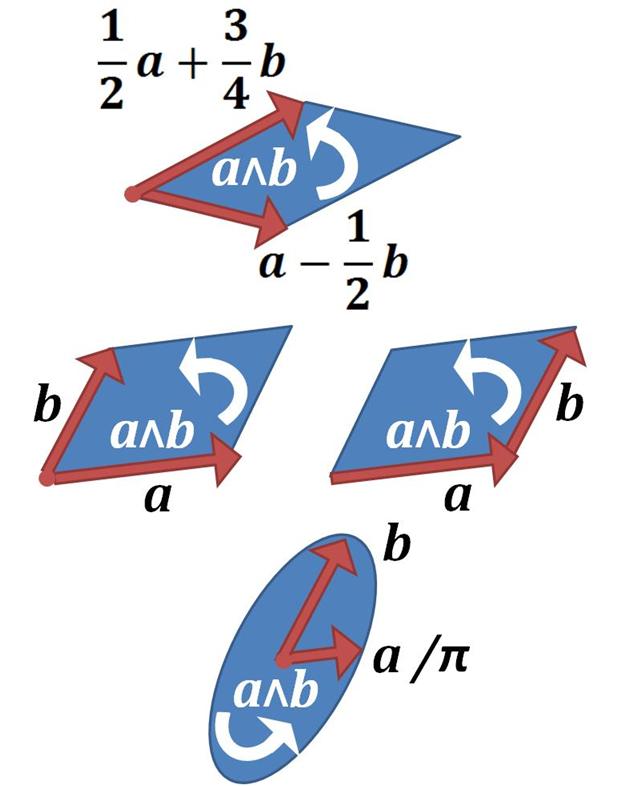

Although bivectors are well-defined in mathematics, we still want to ask the question: How do we visualize a bivector? The answer is: We can represent a bivector as an oriented surface element. Different-shaped surface elements that are parallel to each other and have the same area represent the same bivector. In other words, the same bivector can be depicted in infinitely many ways, as long as they are parallel, have the same area, and have the same orientation.

Parallel surface elements with the same area and orientation represent the same bivector.

In practice, treating a bivector as a vector using the right-hand rule is only applicable in three-dimensional manifolds. This is because only in three-dimensional manifolds does three minus two exactly equal one. In four-dimensional manifolds, since four minus two equals two, we can only dualize a bivector into another bivector, not a vector.

In five-dimensional manifolds, a bivector can be dualized into a trivector, and so on. In an n-dimensional manifold, a bivector can be dualized into an (n-2)-vector.

3 Maxwell Equations in Exterior Algebra

By the way, the electric field is also a bivector. Its basis consists of $\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\wedge \frac{\partial}{\partial x},\,\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\wedge \frac{\partial}{\partial y},\,\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\wedge \frac{\partial}{\partial z}$, involving a time dimension. The reason it doesn’t appear as a “pseudo-vector” is that we only consider space inversion transformations rather than time inversion transformations.

If we consider the electromagnetic 2-form in the cotangent bundle (using natural units):

$$ \begin{aligned} F&=E_x\mathrm{d}t\wedge\mathrm{d}x+E_y\mathrm{d}t\wedge\mathrm{d}y+E_z\mathrm{d}t\wedge\mathrm{d}z \\ &+B_x \mathrm{d}y\wedge\mathrm{d}z + B_y \mathrm{d}z\wedge\mathrm{d}x + B_z\mathrm{d}x\wedge\mathrm{d}y \end{aligned} $$

Since we can raise or lower the indices of a tensor with the help of a metric tensor, we can also write a $(2,0)$-type electromagnetic tensor with the basis formed by the exterior product of $\frac{\partial}{\partial t},\frac{\partial}{\partial x},\frac{\partial}{\partial y},\frac{\partial}{\partial z}$.

However, for now, let’s adopt the $(0,2)$-type antisymmetric tensor (differential form) because it allows us to utilize the symbol $\mathrm{d}$ for the exterior derivative.

Now, let’s consider the current 1-form: $J=-\rho\mathrm{d}t+J_x\mathrm{d}x+J_y\mathrm{d}y+J_z\mathrm{d}z$.

Thus, under the Minkowski metric $\text{diag}(-1,1,1,1)$, Maxwell’s equations can be expressed in a concise form:

$$ \left\{\quad \begin{aligned} \mathrm{d}F&=0 \\ \star \, \mathrm{d}\star F &= J \end{aligned} \right. $$

Here, $\star$ represents the Hodge star operator (also known as Hodge duality).

As can be seen, in the language of exterior algebra, the electromagnetic field is a 2-vector or a 2-form, rather than a vector or a 1-form.

The current is indeed a vector (or a 1-form), though.